Ohio's Toledo Zoo opened a number of innovative new exhibits over the past couple of years, but I find the zoo's dedication to preserving its rich history as reflected in its respect for the vintage Spanish- and Moorish-influenced architecture on its campus equally interesting to me.

We met with Peter Tolson, the Zoo's Director of Conservation and Research, to learn more about the zoo's historic buildings during our most recent visit to the zoo.

Tolson is the zoo's resident expert on the buildings and their history. He sometimes conducts tours of the zoo for architectural enthusiasts and has plenty of stories and insight about the zoo's early days and construction of some of its most iconic buildings.

The zoo has one of the largest collections of buildings constructed during the 1930s under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in a single location. The buildings are a legacy of workers and artisans employed through Federal government programs to create public works projects benefitting the community while employing workers during the Great Depression.

The Reptile House, Museum of Science, Aviary, Amphitheater and the Aquarium are all WPA-built projects.

The Cafe (1925) and the Lodge (1924) even predate the WPA buildings. Visitors can dine in one of the cages in the Cafe, originally home to carnivorous animals like tigers, or book events in the Lodge, formerly the pachyderm elephant building (or "a cathedral for elephants" in the flowery prose of the 1920s), which is now an elegant Conference and special event center.

Tolson told us about Roger Conant, a noted herpetologist who was Curator of Reptiles and later General Curator at the Toledo Zoo during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Conant provided the real spark behind the zoo's work with the WPA during the mid-1930s.

Conant noticed a group of government workers raking leaves in Walbridge Park across the street from the zoo. The workers raked the leaves from one end of the park, then turned around and raked the leaves all the way to the other end of the park.

Conant drew up plans for a reptile house and persuaded government officials to make the new building an official WPA project.

The Reptile house became the zoo's first WPA project, begun in 1933 and completed in 1935.

WPA workers included skilled craftspeople, artisans and architects. Architects drew up plans for several more zoo buildings, which included the Amphitheater (completed in 1936), Aviary (completed in 1937), Museum (completed in 1938), and Aquarium (completed in 1939 and undergoing a renovation scheduled for completion in 2015).

Tolson says that the WPA employed as many as 5,000 workers at the height of construction on buildings at the zoo, and that they set records for speed in the building trades at that time.

The Reptile building is notable because of efforts to carefully salvage and repurpose materials in its construction, making it a "green" building project before that idea was common. Government programs only paid for labor costs, and recycling helped save money to meet budgets.

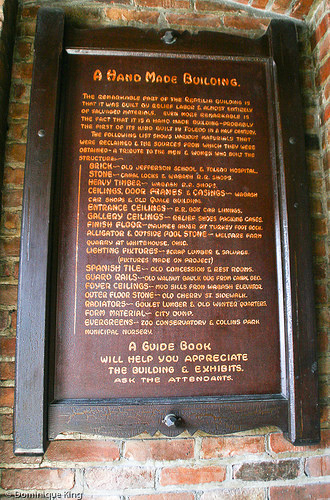

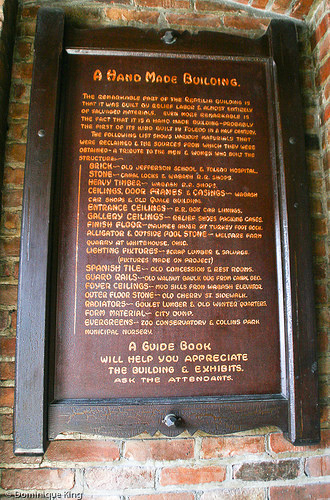

A sign in the Reptile building itemizes some of the salvage materials used in the construction of the "hand made building". Much of it came from old canals and public buildings like demolished schools, hospitals and businesses, or even the town dump.

Building designers used natural light in ways that were innovative for the 1930s such as the use of skylights and, most notably in the Aviary, glass-block bricks.

Painters, sculptors and other artists worked with the WPA, creating murals, statues and other decorative accents throughout the buildings and the zoo.

Forest "Woody" LaPlante worked on many of the murals in the Reptile and Aviary as a 19-year-old WPA and Federal Art Project (FPA) worker. He returned to the zoo years later to spend several years helping restore and recreate some of the same murals after a 1970s "redecoration" destroyed many of them.

Arthur Cox was an English stonecutter who did many of carved animal statues and fountains throughout the zoo. He died of silicosis, likely aggravated by his profession, as he neared completion of the job.

Thankfully, the zoo's buildings didn't suffer the same fate as the murals. The zoological society renovated the older buildings before building newer exhibits in recent years says Tolson.

We saw evidence of this as we toured the construction site at the historic Aquarium's renovation. Workers were modernizing and expanding the interior of the facility while preserving its original foot print and leaving the exterior largely unaltered. Construction on the newer exhibits also seeks to match the facade of the historic buildings as closely as possible.

For a look at the some of the Depression-era architecture in Toledo, check out Toledo: A History in Architecture 1914 to Century's End by William Speck.

Thanks to the Toledo Zoo for hosting us for a tour of the zoo and the exhibit construction sites.

© Dominique King 2014 All rights reserved