Carvings of archers, animals, and other mysterious images at Sanilac Petroglyphs State Park survive to document prehistoric Native American life and rituals for future generations, even as weathering and carved graffiti threaten to obscure this account of early Michigan.

I first visited the petroglyphs years ago with a cousin from California who wanted to see the carvings. We found them, after a two-hour drive to the petroglyph park, locked behind a five-foot fence (which proved no match those determined to see the carvings). The petroglyphs already showed signs of wear and vandalism that continue to concern state officials, the area's Native people, and archeologists.

Over the years, state officials tried protecting the carvings while providing access. Tim and I visited the petroglyphs several years after my first visit, and a sign on the fence instructed visitors to knock on the door of a nearby farmhouse and ask for a gate key if they wanted a closer look.

Docents greeted visitors during our latest visit to the site last year.

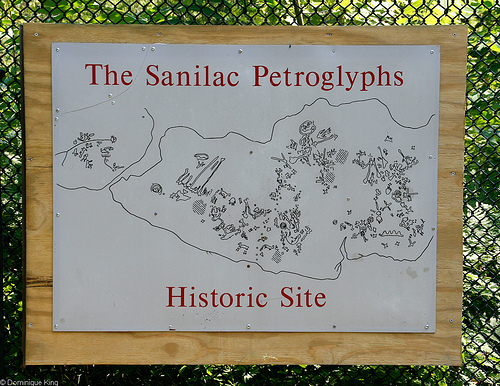

Sanilac's petroglyphs remained hidden for many years as vegetation obscured the 1,000-square-foot sandstone rock containing about 100 images.

Fires across the region in 1881 claimed one million acres of forest and 282 lives, but fire also revealed these petroglyphs that geologists determined to be 300 to 1,000 years old.

Sandstone is soft, so Native Americans easily carved figures into it. The stone's softness meant that subsequent generations found it easy to add their own names, doodles, and other graffiti. You can still readily see some of the petroglyphs at Sanilac, but modern-day graffiti and years of open exposure makes it difficult to see some of the fainter images or differentiate some original carvings from newer graffiti.

State officials tried to protect the Sanilac petroglyphs over the years, but discussions about jurisdiction and funding further protective measures continue to be a concern.

The site was under private ownership for many years, and Native Americans from a reservation in nearby Caro summered there as late as 1900.

The Michigan Archaeological Society purchased the land containing the petroglyphs in 1966, deeding it to the state five years later.

The wooden canopy and five-foot-tall fence I saw when I first visited offered the only protection for the carvings until seven years ago, when the state installed a 12-foot-tall chain-link fence to secure the petroglyphs when there was no onsite supervision.

An article in The Detroit News by Jim Lynch (May 21, 2011) covered the debate surrounding protecting the site, and questions about who should do so.

No one is sure what tribe did the carvings, but members of Saginaw's Chippewa Tribe feel a special connection, and responsibility, to the site, treasuring the petroglyphs and the ancestral wisdom they represent.

Area archaeologists, who say the tribe wants sole control over the petroglyphs and the 240-acre state park at the site, worry about maintaining access to the site and express concern that private ownership would limit scientific study and interpretation of the carvings.

Michigan's Department of Natural Resources currently pays about $15,000 annually for basic upkeep at the site.

Some state officials and archaeologists would like to see a glass enclosure to protect the prehistoric carvings, but with a projected $300,000 tab for such a structure, don't look for it any time soon.

The petroglyphs are still well worth visiting.

The approximately 1/4-mile-long trail to the petroglyphs pavilion is level and accessible for most visitors. The pavilion is generally open to visitors during the summer and staffed with interpreters 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday or by appointment.

Best petroglyph viewing times may overcast days when visitors can use a flashlight to highlight the images, as interpreters did for us when we visited the site last summer.

An easy 1.5-mile interpretive trail loops though forests and past remains of a 19th-century logging camp and historic Native American settlements. The trail is open 8 a.m. until 10 p.m. daily.

Interpreters told me the park has open house events at the petroglyph pavilion in June and August. The first summer open house in 2011 is 10 a.m. until 3 p.m. on June 25 and includes kids' crafts and history displays.

The local Chippewa tribe holds celebrations each summer (set for June 18 in 2011) when they gently cleanse the petroglyphs and offer cultural lessons in the Anishinabe language.

Check out the nearby Thumb Octagon Barn and Agricultural Museum when you visit the petroglyphs.

Want to learn more about the history and culture of Michigan's Ojibwe and other Midwest Native Americans? Check out Enduring Nations: Native Americans in the Midwest by R. David Edmunds, The Ojibwe of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota by Janet Palazzo-Craig, or Art of Tradition: Sacred Music, Dance, and Myth of Michigan's Anishinaabe, 1946-1955 by Gertrude Kurath, Jane Ettawageshik, and Michael D. McNally.

© Dominique King 2011 All rights reserved